The traditional Viennese coffeehouse culture remains a familiar part of daily life. It's part of the streetscape, part of the routine. Rooted in 19th-century social life and still central today, Viennese coffeehouse culture offers a uniquely enduring rhythm in the heart of the city. In 2011, Vienna’s coffeehouse culture was officially recognized by UNESCO as Intangible Cultural Heritage - a tradition that goes beyond drinking coffee and reflects the city’s social and cultural identity.

If you’re in Vienna, you’ll want to experience one of these historic cafés - where writers, composers, philosophers, and politicians once sat, and where the atmosphere has barely changed since. Think Freud, Trotsky, Zweig, and Klimt. Some had their own “regular” tables, where they spent hours reading, debating, and observing.

Historically, these cafés served as neutral social grounds - spaces where aristocrats and workers might sit side by side, reading the same paper and drinking the same coffee.

Legend has it that coffee first came to Vienna after the Battle of Vienna in 1683, when the retreating Ottoman army left behind sacks of beans. At first, locals weren’t sure what to do with them - until a Polish officer, Jerzy Franciszek Kulczycki, reportedly opened one of the city’s first coffeehouses.

A setting shaped by tradition

Many of today’s cafés are located in historic buildings with interiors that have changed little over the past century. Tall windows, high ceilings, parquet floors, marble surfaces, dark wood, and upholstered seating create a calm and composed atmosphere. Some cafés occupy expansive salons with gilded mirrors, stucco ceilings, and cake vitrines that resemble museum displays. Others are more modest but maintain the same quiet elegance. Most of the iconic cafés are located near the Ringstrasse or in the city centre, which reflects the grandeur of the late 19th century. Most share a familiar layout: a main room with a clear sense of rhythm and proportion, designed for lingering. These visual and spatial details are central to Viennese coffeehouse culture, where the setting plays a key role in the overall experience.

Service follows a time-honored routine. Waiters in classic uniforms move with quiet professionalism. Guests are seated and served at the table, and every cup of coffee arrives on a small silver tray, accompanied by a glass of water - a tradition that dates back to the 19th century. Payment is made at the end, and there is no pressure to leave. It’s common to stay longer.

Coffee and Cake: A Cultural Pairing

The coffee menu is consistent across most traditional cafés. The Melange - a mild blend of espresso, steamed milk, and foam - remains the most popular. The Einspänner, served in a glass with a layer of whipped cream, offers a bolder, darker profile. Other classic styles include the Kleiner Schwarzer (single espresso), Großer Brauner (double espresso with milk or cream), and the Franziskaner, a lighter variation topped with whipped cream instead of foam. No matter the style, enjoying a Vienna coffee is as much about the ritual as it is about the drink itself.

In Viennese coffeehouse culture, pastries are just as important as the coffee. Most are ordered by the slice, and many recipes are tied to each café’s identity - often passed down through generations or sourced from long-standing patisserie partners. While the selection varies, you’ll usually find a mix of chocolate tortes, fruit cakes, nut-based desserts, and strudels. The Sacher-style chocolate cake is rich and dense, with a thin layer of apricot jam beneath its glossy chocolate glaze. Apple strudel arrives warm in flaky pastry, usually dusted with powdered sugar. Kaiserschmarrn - a soft, torn pancake, and served with fruit compote, often plum. You’ll also see layered cakes with cream, jam, or nuts, all served on elegant porcelain, often with a spoonful of whipped cream on the side.

Pairing a pastry with a Vienna coffee is a timeless pleasure, and one of the most atmospheric ways to slow down in the city.

Why Viennese Coffeehouse Culture Still Matters Today

Coffeehouses operate from mid-morning to late evening. Guests come alone, in pairs, or in small groups. Some read, others talk. Many simply sit in a setting designed for presence rather than productivity. This slower rhythm of daily life is one of the defining qualities of Viennese coffeehouse culture.

Laptops are rare. These are not working cafés, but places to pause. Printed newspapers are still available in many, often displayed on wooden holders near the entrance.

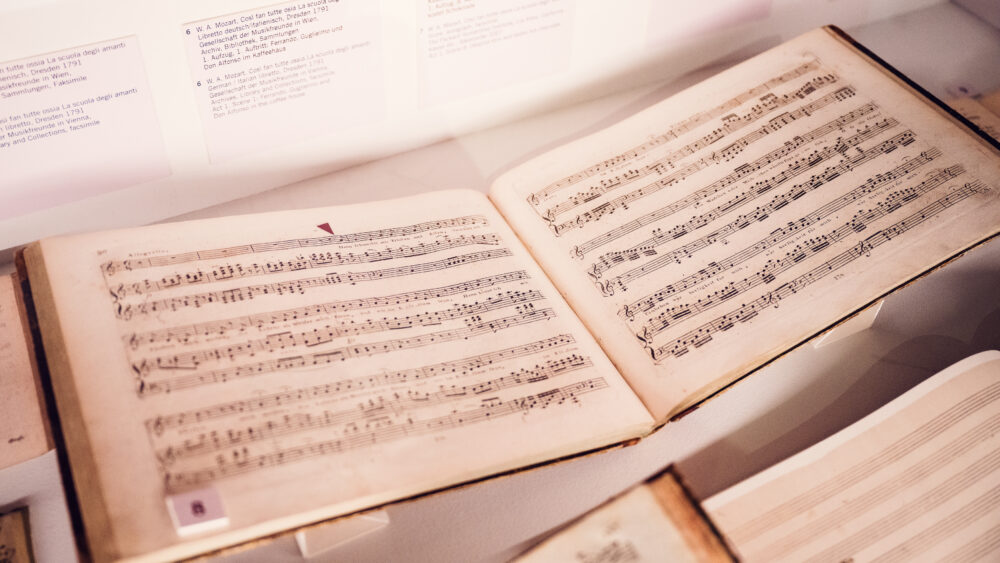

A few coffeehouses still include live piano music - usually on weekends, played softly in the background, adding a quiet formality to the space.

Viennese coffeehouse culture remains an essential part of daily life for locals and a meaningful experience for visitors. These traditional cafés don’t follow trends or chase novelty. Instead, they offer a more deliberate kind of experience - shaped by setting, ritual, and a formality that has lasted for generations. While newer cafés lean toward change, these institutions endure by continuing to do things the way they always have: thoughtfully, patiently, and with quiet pride. Despite changes in the city, Viennese coffeehouse culture continues to offer a consistent and recognizable experience. The Vienna coffee tradition endures because it stays true to a slower, more mindful way of being.

Viennese coffeehouse culture developed as part of everyday urban life. These cafés were never just for special occasions - they became part of people’s routines, offering a steady rhythm in the middle of the city. The setting, the service, and the pace all reflect a cultural preference for taking time, whether for reading, writing, or simply doing nothing at all.

Looking for a place to experience it yourself?

If you're curious to see how Viennese coffeehouse culture lives on today, there are a few cafés that still carry the tradition beautifully. Think grand interiors, signature cakes, and that quiet sense of timelessness.

Just across from the State Opera, Gerstner – once a K.u.K. Hofzuckerbäcker (Imperial and Royal Court Confectioner) – combines imperial-era charm with light-filled modern elegance. The upper-floor salon offers beautiful views and a calm setting for coffee and cake.

Located next to the Opera, Café Sacher serves the original Sacher-Torte in a richly upholstered, old-world setting. It’s a classic stop for those seeking a piece of culinary history.

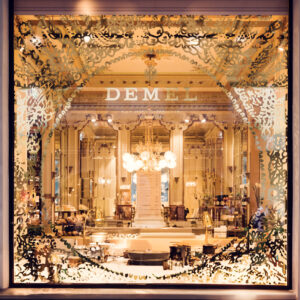

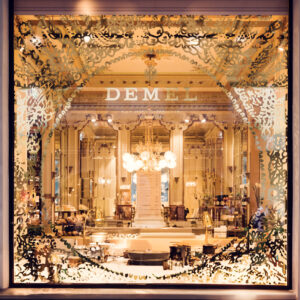

Once a k.u.k. court confectioner, Demel is known for its elaborate pastry displays and elegant interiors. The open kitchen offers a glimpse into the craft behind its traditional cakes.

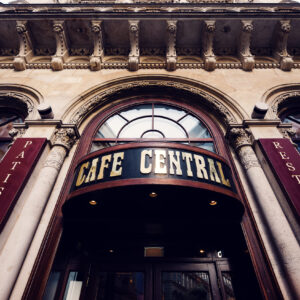

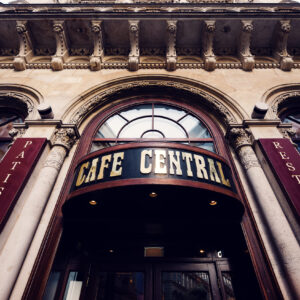

A historic meeting place of poets, thinkers, and politicians, set in a grand former palace. Its vaulted ceilings and quiet formality make it one of Vienna’s most iconic coffeehouses.